Unnamed woman skiing at Mount Seymour in 1950. The onlookers suggest she may be in a race.

British Columbia Mountaineering ClubWith her sleeves rolled up and her backpack full, this “woman in hiking gear” looks like she might be on longer day trip or even on route to an overnight camp or cabin. Today, she would perhaps be in comfortable and functional leggings, t-shirt and baseball cap. In 1916 though, she was wearing what any respectable woman wore when hiking — a long skirt and an attractive hat to keep out the sun.

Location unknown.

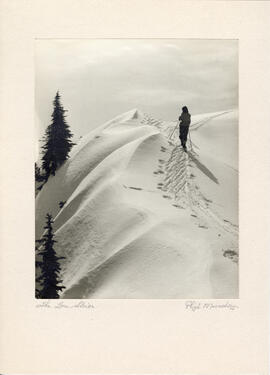

Charles ChapmanWith no crowds to compete with and high above the clouds, how was this skier at Mount Seymour enjoying their day?

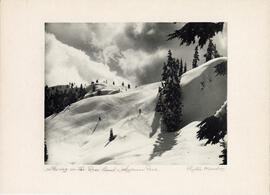

Phyllis MundayFor most people, skiing involves mechanical help to get upslope. After all, the fun part is coming down, not climbing up. But when the only way to get to the top is on your own two feet, is the idea less appealing? For the early Vancouverites who hit the slopes, the answer was no.

Even before gondola cars, chairlifts or access roads, winter in the North Shore mountains was fun, even if people had to hike to get there.

With a winter wonderland on Grouse, Seymour or Cypress mountains, it is no wonder that the settlers of the Vancouver area made their way to the slopes for some fun. Without easy access to the slopes, many skiers built cabins. After all, hiking up each time they wanted to ski was no easy feat. A cabin meant they could enjoy the slopes for longer before the hike back down to the city.

The cabins helped forge a tightknit ski community who ate, partied and skied together. The skiers helped each other to build cabins when someone new came along. This life was so appealing that at one point there were over three hundred cabins on Mount Seymour alone.

As time passed, it eventually became easier to get to the resorts thanks to roads and the Grouse Mountain gondola. Once there, chairlifts and tows made it easier to reach the tops of the peaks. In 1948 though, there was a helicopter that flew skiers to the Grouse Mountain Chalet, as is seen in the newspaper clipping in this selection of archives. James Adam Craig’s reminiscences of his time skiing at Grouse Mountain and Hollyburn also give a great insight into the lives of skiers in the 1930s and 1940s.

As access improved, skiing became a hobby for even more people. From clubs and races to lessons for kids and advice on equipment, all found in the archives, there were many similarities to modern ski life.

It seems there was a lot of love around Gertrude Wepsala. Known to many as Gertie, she was a well-loved, well-respected ski champion. Or as the Montreal Standard called her, "Canada's Gertrude." "Canada" may have loved her, but her home slopes were the North Shore Mountains.

She loved to ski. She trained hard. She skied hard. She posed for photos. Not surprising then that the media also shared in that love...their love for her.

G. B. Warren, James John Trorey, and Atwell Duncan Francis Joseph King display a Union Jack flag on the summit of Mount Garibaldi, having claimed the first recorded ascent in 1907.

Also on the expedition, were Arthur Tinniswood Dalton, William Tinniswood Dalton, and T. Pattison.

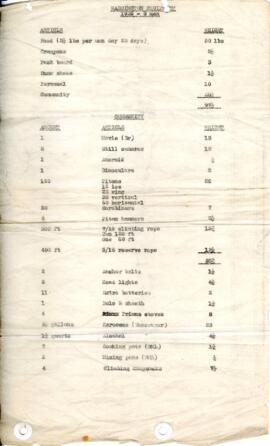

British Columbia Mountaineering ClubOne rubber bath curtain, one pair of pliers for cooking, two hot water bottles, and one can opener — better hope the can opener did not get lost. These are just some of the many items listed for an eight-person expedition to Mount Waddington in 1935.

Also included is the food allowance for six men for twenty days on Mount Waddington in 1936. Though not only is it the food allowance list, but the rationing of matches and toilet paper — with each man allowed ten sheets per day.

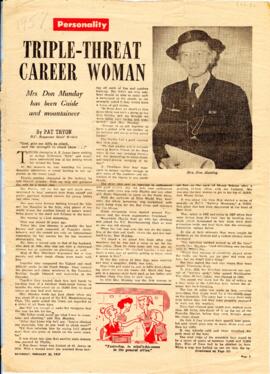

British Columbia Mountaineering ClubThree things were important to Phyllis Munday — her family (husband Don and daughter Edith), mountaineering and the Girl Guides. She poured her heart and soul into them, becoming beloved in all three areas.

This newspaper article describes her life and her loves over five decades from around the time her father told a young Phyllis "you've climbed one mountain, why do you want to climb more?". If ever there were "famous last words," it might be those.

Brian [last name unknown], [unknown] and Gerry Butler (far right) take part in a training session of stretcher raising at Lighthouse Park, West Vancouver. Year unknown.

North Shore RescueItem F223-S3-f1-C-A130 shows a photo of Mount Garibaldi from Mount Mamquam. In this tracing, Neal Carter has shown in red the route taken across the landscape.

The tracing is part of a photo album he made showing peaks of the area.

Neal CarterItem F223-S3-C-A10 shows a photo of Castle Towers to Carr Mountain from Red Mountain. In this tracing, Neal Carter has shown in red, the routes taken across the landscape.

The tracing is part of a photo album he made showing peaks of the area.

Neal CarterUnknown mountaineers on the summit of Black Tusk (2319 metres) in 1914. The peak was first climbed in 1912, and although it is not known when the first woman reached the summit, it is likely that the woman in this photo may have been one of the first; being followed in later years by many more.

Charles ChapmanThree mountaineers pose at the foot of Sphinx Glacier, on the eastern shore of Garibaldi Lake, in 1917. Their journey there was probably part of one of the BC Mountaineering Club's summer expeditions. Even today it is not an easy place to reach.

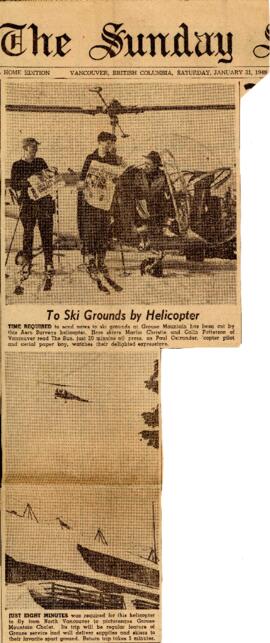

British Columbia Mountaineering ClubIt could be said that this was heli-skiing in its infancy. If hiking up Grouse Mountain with skis on your back did not appeal, then how about a helicopter?

In 1948, Grouse Mountain began a helicopter service taking supplies and skiers to the slopes. At only a five-minute journey, it beat the long, steep hike to get there.

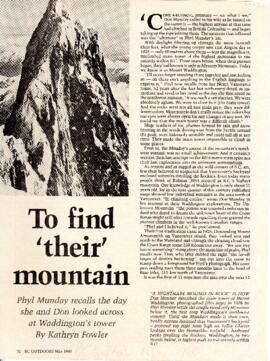

"A nightmare molded [sic] in rock" was how Don Munday described the main tower of Mount Waddington. Still, this was "a nightmare" that he and wife Phyllis Munday were out to get the better off as they faced their fears.

This is a first-person account of their journey to the northwest summit of Mount Waddington. They may not have reached the higher main tower, yet their climb took them higher than anyone was known to have climbed in BC at that time.

“Three mountaineers around make-shift stove” in 1907. Location unknown. The photo caption may have called these young men mountaineers, but were they mountaineering or actually camping close to home?

What the photo does show though is that wherever they were, they did seem keen on bringing some home comforts, like the chance to boil water for what was probably a nice cup of tea.

Charles ChapmanFor a woman who spent much of her early life in the mountains, it is no wonder that her thoughts of the afterlife took her back there.

Here she describes the place she thought her sprit would go to after her death. This piece makes it clear that despite the years passing, the mountains still held a large place in her heart.

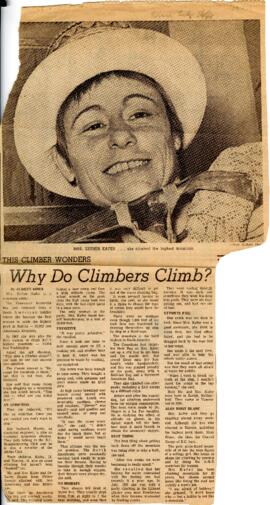

Phyllis MundayFor a woman afraid to climb a ladder, but who is addicted to climbing mountains, including Bolivia's 7000 metre (23,000) foot Ancohuma Mountain, the question must surely be asked — why?

This 1968 newspaper article and interview with Esther Kafer explores her addiction of climbing mountains and the journey to the summit of Bolivia's tallest mountain.

Esther KaferMembers of the BC Mountaineering Club spent summers among wildflower meadows near Black Tusk and Garibaldi Lake. Surrounded by such beauty, it is no wonder they fell in love with this area and wanted to see it protected from natural resource extraction.

This passion for place led to their advocacy for the creation of Garibaldi Park.

Getting closer to the summit of Mount Garibaldi and to achieving the first successful recorded ascent of the mountain. The mountaineers are roped up below the main peak. The party are Arthur Tinniswood Dalton, William Tinniswood Dalton, James John Trorey, Atwell Duncan Francis Joseph King, T. Pattison, and G. B. Warren.

British Columbia Mountaineering ClubThe party of mountaineers who plan to make the first successful ascent of Mount Garibaldi. Here they are about to set out for the mountain, having passed Squamish. They are equipped and ready for the climb. From left to right: Arthur Tinniswood Dalton, T. Pattison, James John Trorey, A. King, and G. B. Warren. Taken in 1907.

Missing from the photo is William Tinniswood Dalton who is perhaps taking the photograph.

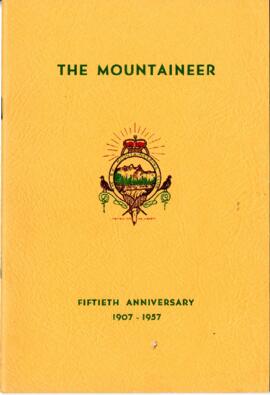

British Columbia Mountaineering ClubWhen the BC Mountaineering Club hit the age of fifty, the members chose to produce a booklet of memories, and fortunately for us today, we can read them here.

This is a great account of the early years of the BCMC — memories of the intrepid explorers who made the mountains their home-from-home.

- Cabins, Camps and Climbs, 1907-1911, by Frank H. Smith

- Early Days of the BC Mountaineering Club, by R. M. Mills

- Recollections, by Charles Dickens

- Reminiscences, by Professor John Davidson

- The Conception and Birth of the Vancouver Natural History Society, by Professor John Davidson

- The Story of Garibaldi Park, by L. C. Ford

- Some Reminiscences of 1920-1926 With the BCMC, by Neal M. Carter

- Snow Peaks, Mount Judge Howay, by Tom Fyles

- Robie Reid, First Recorded Ascent, June 1925, by Elliot Henderson

- Waddington Diary - 1936, by Elliot Henderson

- Waddington Area - 1956, by Jo Yard

- Anniversary Peak, by Roy Mason

- Bushwacking, by R. A. Pilkington

- A Mountain (song), by R. Culbert

It is slow progress without a chairlift or tow rope. Step by step, the only way to ski down is to hike up first, as this skier is doing on Mount Seymour in the 1930s.

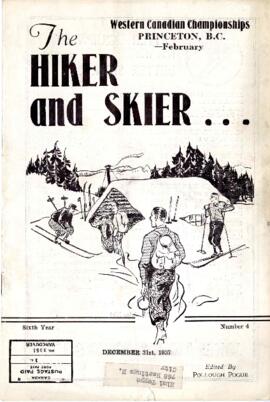

Phyllis MundayThe Hiker & Skier was a twice-monthly magazine that covered hiking, winter sports and outdoor life in the North Shore Mountains. Updates from ski clubs, ads for businesses selling clothing or equipment, and tales from ski trips further afield are all to be found in these pages. Without web pages or social media, magazines like this were the way to find out what was going on in the world of outdoor adventure.

Breakfast time, camp style in 1909. It looks like their campfire might be just off to the right, with the smoke billowing into shot. If so, maybe they are having a hot breakfast as they warm or dry their clothes on makeshift drying posts on the right of the photo.

Charles ChapmanNeal Carter and some of his fellow BC Mountaineering Club climbers had a goal to reach the summit of Mount Tantalus. Their “assault” on the mountain was not successful. They got close but not close enough to reach the top. The photos in this album show their multi-day journey camping in the snow, crossing crevices, and traversing near-vertical snow slopes, only to have the mountain — twice — foil their goal.

A century ago, mountaineers saw mountains as a place to “conquer.” The use of the term “assault” here reflected the physical challenges that mountaineering presented and the need to overcome them. Today, with a more holistic view of relationships with the land and a reflection on colonial attitudes, “conquering” mountains is a concept being relegated to the history books.

Neal CarterPerhaps another name for Mount Tantalus could be Mount Tantalizing. This account of the exploration of the Tantalus Range shows that for some climbers they got close but not close enough.

In the meantime, these mountaineers climbed other peaks and gave names to features that are well known today, such as Lake Lovely Water.

After a hard day's climb, who could ask for more than dinner with friends? This photo from the "dining tent" in 1917 was likely from one of the BC Mountaineering Club's summer expedition camps.

Chatting around the table, they were likely planning their next day. But were they also thinking of how they would like to name peaks, or sharing stories of other climbs? It must have been meals like these that cemented many lifelong friendships within the club.

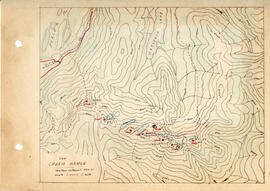

British Columbia Mountaineering ClubThe first European settlers who explored the mountains around Vancouver had no maps. Doing their own surveys and making their own maps formed part of their expeditions.

This hand-drawn map of the Mount Cheam area in the Fraser Valley, made by Neal Carter would have been one of the first to be made. The map is part of a photo album he made showing peaks of the area.

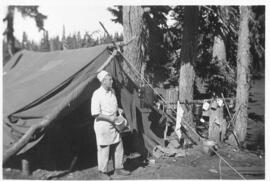

Neal CarterThis photo was taken in 1935, but the location of this camp kitchen is unknown. It was probably for a BC Mountaineering Club summer expedition and may have been their camp at Black Tusk Meadows. With a group of hungry mouths to feed after a long day's climb, having a camp cook was essential.

A bugle hangs on the line by the tent. The cook would have used it to call the campers to the dining tent when their food was ready. That sound must have been a joy to hear for the campers.

British Columbia Mountaineering ClubA sense of adventure was not the only thing that drove early settlers to explore the mountains. Many felt attracted to the plants, insects, birds and other animals they found. For them, summer expeditions were a time to research as well as climb.

The BC Mountaineering Club had a Botanical Section that at one time had more members than active mountaineers. In 1918 they joined with Vancouver’s Arbor-Day Association to form the Vancouver Natural History Society.

In this photo, a botanist is at “work” in his tent in 1917. Although the location is unknown, it is possible he is on a summer expedition to the Black Tusk meadows area.

Holly (last name unknown), Nellie Chapman and two unnamed mountaineers on the slopes of Black Tusk. Nellie explains in the photo caption that she and Holly “climbed part way up the chimney and through the shale which slid from them”, which they found to be “rather exciting”. She also notes that the snow on the downslope is from a “moving glacier”. Taken in 1910.

Charles ChapmanWhile some Alpine climbers may have had porters to carry champagne, BC Mountaineer Club members had no need for this, being surrounded by "streams and lakes." After carrying a seventy pound load though, the mountaineers could perhaps be forgiven for wanting something "stronger" than water.

In these memories of mountaineering in the 1950s to 1970s, James Adam Craig describes his activities in the mountains, including some of the gear and food that mountaineers took on trips.

James Adam CraigClimbing the Lions in an "old suit and pair of shoes that were no longer decent enough for ordinary wear," and being the first recorded climber of the East Lion gives some clue as to the contents of this article.

Written by John Latta, it describes a six-day expedition in 1905 of him and his brothers William and Robert as they decided to climb the Lions. They were all aged around twenty and had no experience, making them either brave or foolhardy — or both. They were not the first known climbers of the Western Lion, but they were recorded as the first to climb the Eastern Lion.

"With a backhand flip, nature would have wiped out all of us, but for the radio, and Flt. Lt. Cameron's wish to miss the early-morning sea fog."

The "nature" in question here is not an avalanche or rock fall, but a massive tidal wave, caused by a destructive earthquake. This drama marked the end of the 1958 (BC) Centennial Project Expedition to Mount Fairweather.

This account gives a wonderful insight into the planning and implementation of this expedition, including their lucky escape from death.

British Columbia Mountaineering ClubA CBC producer and cameraman joined the 1958 BC Centennial ascent of Mount Fairweather. Inexperienced as they were, their tenacity seemed to be intact as they made it across the Fairweather Glacier to reach Base Camp — no small feat in itself. From there, the mountaineers continued onwards for the actual ascent.

This article charts both the climb, and the views of the journalists on this extraordinary journey.

This photo is aptly named "Summit Solitude - Seymour". It is not known who the lucky person is surveying the view from the cairn at the main peak, but hopefully they enjoyed what they saw.

Phyllis MundayThis photo was taken in 1945, though what month is unknown. What this means though is that World War II was either still ongoing, or not long finished.

Either way, thoughts and emotions brought by war would have been front and centre in the minds of Vancouver residents. Skiing across a winter wonderland must have been good for the soul and a chance to escape the wartime stressors.

British Columbia Mountaineering ClubThis skier looks to be traversing and even climbing the slope, not skiing down it. Without chairlifts or tow ropes, the only way up a slope was the hard way — muscle power. This photo from Rose Bowl on Mount Seymour in the 1930s could be a skier doing that.

Phyllis MundayGertie Beaton (nee Wepsala) was a ski champion who wrote a newspaper column in the 1950s. It is possible that this document is one of her typed drafts and handwritten edits.

In it she talks of a proposed ski development in Garibaldi Park, with “a luxury hotel at the 6,000 foot level.“ Could this be the ski resort at Brohm Ridge that never happened? Interestingly, she questions the logic of this given the unpredictable weather.

She also talks of the ski season across the province and across the border in the United States. She certainly had her finger on the pulse of the ski world.

Gertie Beaton (nee Wepsala)Who would not want to pause for a while and take in the view while skiing above Mystery Lake in Seymour Park?

Phyllis MundayThe Vancouver skiers of the 1930s and 1940s were a "hardy bunch." With no road or gondola, it was a hike — with skis — for around six hundred metres (~2000 feet) to get to the slopes. The fortunate ones had cabins and could extend their stay, getting the most from that gruelling hike. For the rest, they hiked up, skied, then had to hike out again.

Here, James Adam Craig recalls his winter memories, of Whistler, Grouse Mountain, Hollyburn, and in Washington, learning the Christiania ski turn, and the equipment that took him onto the slopes.

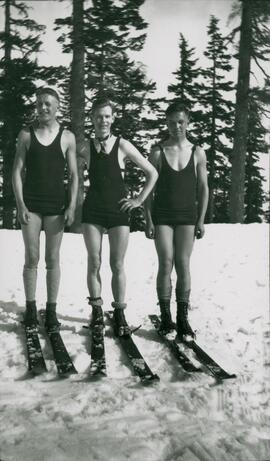

James Adam CraigIt must have been a warm, spring day when this photo was taken. Nip Stone, Doug Manley and Hubert Ackroyd (left to right) pose in wool swimsuits on Grouse Mountain.

Nip Stone ski-jumped for Canada in the 1932 Winter Olympics at Lake Placid, New York.

Here, Ev and Alex Blain (right foreground) pose for a photo at an unidentified location, believed to have been taken between 1935-1937.

What is intriguing about this photo is the shininess of the man's pants. Were they soaked, or were they waterproof? Woollen clothing was common then, though some people used to wax fabrics for waterproofing. But it is hard to tell from this photo if he is dry and comfortable, or wet and freezing because the moisture on his pants has frozen.

With the sun low in the sky casting long shadows here, this looks late in the day. Whoever this man was, was he wondering how many runs he had left before it got dark?

While terrain parks offer excitement on the slopes today, in years gone by there were ski jumps to give a rush of adrenaline.

This photo shows the ski jump at Mount Seymour.

![[Tracing of "Mount Garibaldi from Mount Mamquam"]](/uploads/r/passion-for-adventure/8/4/0/840deb8b53722309155fe8d589dcbd0252ec6186957bac3d1ffbca108cd57d2f/F223-S3-f1-C-A13_142.jpg)

![[Tracing of "Castle Towers to Carr Mountain from Red Mountain"]](/uploads/r/passion-for-adventure/6/0/9/6093aaf462f2b53cea08b0cf69281d91fd700ceacfad780d5d7b56144d350e95/F223-S3-f1-C-A9_142.jpg)

![[The First and Second 'Assaults' on Mt. Tantalus - Selected Pages]](/uploads/r/passion-for-adventure/7/9/7/797462796339ffda6414cc71b3bd35b7a21bb621e643ffe2bbb61267fab0b6c3/F222-A2-_p5-12__142.jpg)

!["The Black Tusk. Garibaldi: Holly and I [Nellie Chapman] climbed part way up this chimney and through the shale which slid from us... rather exciting. Snow in side slope of moving glacier. 1910"](/uploads/r/passion-for-adventure/9/3/7/937418a4305e3393cb9bc6fd89b2fb13aca91cb5feb8162fe780124887d0e155/F205-64-023_142.jpg)

![[Snow-Covered Trees, Seymour]](/uploads/r/passion-for-adventure/0/f/4/0f40fd887df59d3f10761c89058cc1296ed1c1a8277746664e3624394d3ad88c/5686-12-L_142.jpg)

![[Snow-Covered Trees, Seymour]](/uploads/r/passion-for-adventure/3/8/3/383501b68f886a913c21da7f9857055e13c286056bf88d9e0be47bae74973afe/5686-11-K_142.jpg)

![[Snow-Covered Trees, Seymour]](/uploads/r/passion-for-adventure/0/6/5/065dc39302a0bb43adbe7fcc88473e1a97ea2f0453fee64af00e6025232dd9c9/5686-3-C_142.jpg)

![[Snow-Covered Trees, Seymour]](/uploads/r/passion-for-adventure/6/f/0/6f07b1bb59746929254ea132fc09f6b6a963c4a5be1cc88e43d912af68b2cd63/5686-4-D_142.jpg)

![[Skiing in Garibaldi Park]](/uploads/r/passion-for-adventure/7/8/f/78fbb69c12eedd44c1896ff3320c74da6c6ea2f89e4870c0431f41428e54bd1b/F229-_2-9_-i1_142.jpg)

![[Skier on Slope]](/uploads/r/passion-for-adventure/2/9/f/29fb5ee6bbb9cad92853bb7126f664a6271edca8667b266c06f0f8b6c5710874/F205-32.021_142.jpg)